What are we to make of Jesus’ absence at the end of Mark’s Gospel? The women find the tomb empty and a young man tells them of the resurrection. The youth then instructs them to tell the disciples that Jesus is going ahead to meet them in Galilee. But the women flee from the tomb… and say “nothing to anyone, for they were afraid.”

That’s it. The end. No Jesus.

The earliest manuscripts we possess do not contain anything after 16:8. 16:9-20 appears to be one attempt to erase the uneasy feeling the ending at 16:8 leaves.

Why would the author leave his audience anticipating an appearance of the resurrected Jesus that, as far as the narrative is concerned, never comes? The simple and surprising answer is that it detracts from his message. By not recording a resurrection appearance, Mark has placed more weight on other apparently more important details.

What could be more important?

Before I answer that, I need to point out Mark’s special enigmatic quality. Its typical of Mark not to explain his meaning but to leave a trail of bread-crumbs for his readers to follow. Mark shows. He doesn’t typically tell. Here’s an example: Mark never identifies John the Baptist as Elijah. What Mark does is describe John as dressed in a leather belt (Mark 1:6), which if you know the OT will point you to Elijah (2 Kings 1:8). Mark also presents John’s death through the machinations of a royal couple who, if you know the OT, will seem surprisingly reminiscent of Elijah’s enemies, Ahab and Jezebel (Mark 6, 1 Kings). Mark even quotes from Malachi and alludes to the promise of Elijah’s coming at the end of that book (Mark 1:3, Mark 9:9-13). But not once does Mark explicitly say that John the Baptist was Elijah or an Elijah figure. That explicit connection is found only in the other gospels. Matthew, for instance, adapting Mark, makes this identification plain (Matthew 11:14). Mark, however, is obscure. He leaves his readers to follow clues to arrive at this conclusion. From this example and other like it, its clear that Mark expected a great deal of knowledge and sensitivity on the part of his readers.

Surprisingly, Mark spends most of his short ending returning to the stone at the entrance of the tomb – three times in fact. In 15:46, Mark informs reader that Jesus’ tomb “had been cut out of the rock” and it was sealed by rolling a stone against the entrance. And when the women arrive in 16:3, three verses later, they wonder, “who will roll away the stone?” The answer comes in the following verse when they discover the “stone had been rolled back.” Mark further adds “that it was very large.” Why such stress on this detail? Remember Mark chooses to focus on this detail rather than a meeting with the resurrected Jesus. Why?

Interestingly, the only other place in Mark we read about stones is in the section dealing with Jesus’ judgment of Jerusalem and the temple (Mark 11-13). There we find two scenes referring to stones. The first occurs at the end of Jesus’ parable of the tenants and deals with the reversal of fortune for the rejected stone (jesus and or the “others”) in the coming destruction of the temple. The next appears less than a chapter later at the introduction of the Olivet Discourse. The disciples admiration for the stones of the temple, prompts Jesus to remark that they will all be thrown down. Again the readers are pointed to a reversal of fortune for stones brought about by the coming destruction of the temple. For these two references, at least, stones are clearly connected with Jerusalem’s destruction.

Is it possible then that the rolled stone from the tomb’s entrance points to the same meaning? In the Olivet Discourse (Mark 13), Jesus explicitly connects the coming destruction of Jerusalem and the temple with the coming of the Son of Man, which is a clear reference to Daniel 7. In Daniel, that event brings about an end to the four beastly kingdoms and the establishment of a kingdom without end, represented in the coming of the Son of Man. But readers familiar with Daniel should in this reference also recall Daniel 2 and its related prediction. There, we find an idol/image with four different metals, also representing four kingdoms, which are likewise destroyed and supplanted by an everlasting kingdom. But instead of the Son of Man, however, the image in Daniel 2 is destroyed by a stone cut out from the mountain without human hands.

Daniel 2’s description of the stone matches in several ways Mark’s depiction of the tomb and its entrance. Daniel says it was a stone cut out from a mountain (Daniel 2:34, 45) while Mark tells his reader the apparently otherwise-needless detail that the tomb had been cut out of the rock (Mark 15:46). Daniel also points to the divine origin of the stone which was “cut out by no human hands” just as Mark seems to point to some invisible hand which has rolled the “large” stone. All this appears to suggest that the destruction of the temple and the establishment of the eternal kingdom have begun in the resurrection of Jesus. The rolling of the stone is the first movement of the kingdom that has no end.

How often do we see and yet not truly see? If the Sixth Sense and its twist ending are any indication it occurs more often than we think. Even in its final reveal, there’s a meaning most people still miss.

Here’s how it works.

After Dr. Malcolm Crowe is shot by a former child patient, He spends the rest of the film trying to redeem himself by helping the young Cole Sear who shows many of the symptoms that plagued his former patient.

Cole is at first wary of Malcolm and Malcolm uncertain of himself. But over the course of the film, Malcolm builds a relationship with Cole until at last, halfway through the film, Cole confesses that he’s afraid because he can see dead people.

Malcolm eventually comes to believe Cole and in the end teaches him to see this ability not as a curse but a gift.

The real bombshell, however, occurs in the closing scene of the film when Malcolm, along with the audience, realizes that he’s one of the dead who sought his patients help. Cole wasn’t just speaking TO Malcolm, he’s talking ABOUT Malcolm. And in this eye-opening moment, the film quickly recaps a number of scenes in which we now see how each was wrongly perceived.

Although it appeared Malcolm had spoken to others in the film, in reality no one has spoken to him since his shooting except the young boy. M. Night has left scenes ambiguous, allowing us to mistakenly grasp their significance until the film’s end.

The Sixth Sense links the symbolism of blindness and sight, darkness and light with death and life. For instance, We remember how the film ends but forget how it begins with a slow turning on of a light bulb, a symbol of the revelation to come. And it’s only when Malcolm sees and or realizes he’s dead that he’s ushered into the light – the afterlife.

But it’s Cole who has the gift of sight and the film turns on what he can see. A sight which is in part symbolized by the large glasses he wears when Malcolm first meets him. But his name Cole Sear is just as symbolic. Sear may be spelled S.e.a.r. but it’s also pronounced Seer. And it’s no coincidence that’s it’s Malcolm he sees. Col is in the middle of Malcolm’s name. And pronounced with a soft C, we can see that it too is a play on the words. Cole Sear is a Soul Seer. He see’s Malcolm’s Soul, his inward being.

The Sixth Sense is about seeing beyond outward appearances to the reality that lies beyond. Which leads us to the twist most people still miss. Who else doesn’t see that Malcolm is dead. We, the audience. We only see what we want to see. And in our blindness, we’re just as dead as Malcolm.

Before Christopher Nolan was known for making meta-cinematic movies, like inception, where the movie is about movies and the hidden messages filmmakers speak through them. M night gave us this movie, the Sixth Sense, in which he showed the disparity that often exists between the surface of a film and its true significance.

Here the peeling back of a facade opens a father’s eyes to his own heartbreaking reality and at the same time graciously raises his other daughter from that same death.

The question is, what have we missed?

Ever since its release in 2004, Christians have been clamoring for a sequel to the Passion of the Christ, hands down, the bloodiest Christian movie ever made.

“Why did you make this film… I think there’s a tendency for all of us to take that event for granted. And cinematically I think its been sanitized a fair bit so that it becomes ineffective, ineffectual, not emotional and I wanted to illustrate the extent of the sacrifice.”

Many reviewers were disgusted with the Passion’s bloodshed, calling it an epic snuff film, but Christians saw in it God’s manifested love for all humanity. A meaning which Gibson, in the film’s opening quotation, invited audiences to see.

The Passion went on to become the highest-grossing independent and rated R film, earning 610 million dollars worldwide. It’s not surprising, therefore, to see why Christians want a sequel. But they’ve totally missed the one Gibson gave them.

In 2006, Gibson followed the Passion with Apocalypto, a story which is a continent, culture, and millennium removed from the crucifixion. Apart from the arrival of the Spanish at the film’s end, nothing in it appears to do with Christianity, even though just as bloody as the Passion of the Christ.

Christians understood the Passion’s brutality but they could not swallow Apocalypto’s. According to one Christian reviewer the Passion’s “very subject matter – crucifixion – lent itself to such explicit imagery…” But concerning Apocalypto’s violence, they had to conclude, “with no theological framework to guide it, it’s difficult to see how this gruesome film could be recommended for Christian audiences of any age.”

The irony is striking since Gibson has gone to great links to connect the two films.

Language

One of the most obvious is in language. To date, Gibson has directed five films and yet only two, the Passion and Apocalypto, have been filmed using ancient languages which few speak or understand today.

Title

The title is also telling. Apocalypto is Greek for “I reveal” and is related to the Greek word Apocalypse, Revelation, the last book in the New Testament. If we consider that the Passion was Gibson’s meditation on the Gospels, at the beginning of the New Testament, Apocolypto suggests itself as a corresponding bookend.

Echoes

But even more substantial are the many ways Apocalypto echoes the earlier film. Opening, for instance, like the Passion, with a white text quotation on a black background from which it fades to a slow zoom on a wooded landscape. Here, Apocolypto introduces Jaguar Paw and his tribe who like Jesus are hunted, captured, and ripped from the forest to endure an agonizing journey, carrying a beam to a city and a hill of execution where they’re laid on their backs and pierced through as a sacrifice. Here, the film also echoes the Passion in the darkening of the sky.

But here’s where the echoes end. The passion is nearly over. Jesus is taken down from the cross. And in one final scene, rises from the dead. But Apocolypto goes on for another half in which Jaguar Paw escapes and races back to save his wife and child in the place where the film began. There he must confront and kill his enemies, one by one, before the waters rise too high. But the arrival of the Spanish, distracts the last of his pursuers. And after rescuing his family, together they seek a new beginning in the forest.

Theological Framework

Apocolypto and the Passion are two sides of the same archetypal coin. The Passion may begin in the Garden of Gethsemane but its more importantly an allusion to the Garden of Eden. The serpent suggests that Jesus is here undergoing the temptation of Adam and Eve. Whose failure, according to the Bible, cast the mold for every human person. But Jesus rejects the serpent and thereby begins to break and remake that mold. He freely surrenders and endures mankind’s banishment from garden / the curse of suffering and death, so that by sharing in our suffering he might share with us his resurrection and victory over sin. His new humanity. Thus after death, he rises naked, as Adam and Eve did before the fall, the symbol of humanities return to the garden.

The Passion, therefore, isn’t just a story of a brutalized man. It’s the story of how the only innocent man suffered to become the representative of Everyman. And it’s Everyman, that Gibson shows us in Apocolypto. That’s why it too begins with an allusion to the Garden of Eden, seen in the lush foliage of the forest, the happiness and near nudity of its inhabitants as well as a story echoing Genesis’ account of creation and man’s fall.

“I saw a hole in man’s heart…

This is the story of humanity and Apocolypto. And the city which takes Jaguar Paw and his tribe captive is the embodiment of man’s corruption and fall, subjugating people and nature in it’s perpetual quest for more. The fact that Gibson has pulled the film’s opening quote from something which was origina lly said of ancient Rome, indicates that the city represents more than one particular society. And in the pile of bodies, we’re shown an allusion to the destruction wrought by other empires. In fact, Gibson has said that the film is equally about the destruction wrought by the United States right now.

And its in this symbolic city that Jesus repeatedly gives himself, reversing man’s selfish trend. While some have called the Passion an anti-semitic film, its with and for the Jews that Jesus actually suffers. Isaiah 53 is the climax of a much longer passage in which God promises to return the Jews from their war captivity in Babylon. And the God’s servant suffers with Israel in their exile in Babylon to return them to the promised land. The fact that the word Passion (to suffer) is closely related to the word ComPassion (to suffer with) shouldn’t be missed. Jesus isn’t just one man suffering. He is Everyman suffering. And in Apocolypto, Gibson reinforces Jesus’ Compassion in the Passion by comparing and contrasting scenes like these. The graphic violence of these films is intended to remind us of the real world in which real humans actually experience these things. And the real God who endured nothing less with and for them.

And through his comPassion he returns humanity to the garden.

This there-and-back again plot is central to the bible, occurring again and again, representing man’s plight and hope for redemption. Jaguar Paws second half escape is symbolic of man’s struggle to find salvation in fleeing the selfishness of the city. Gibson also appears here to be alluding to William Golding’s Lord of the Flies but discussion of that will have to wait for the comments below.

Deus Ex Machina

This leads us to the film’s end which has been criticized as a Deus Ex Machina, a plot device whereby a seemingly unsolvable problem is abruptly resolved by an unexpected intervention of some new event, in essence lazy storytelling. Nothing in the film prepares the audience for the arrival of the Spanish.

But its important to note that the same was also true of the resurrection in the Passion of the Christ. While the rest of the film focuses on Christ suffering, the short resurrection scene at the end of the film occurs abruptly and appears tacked on. The film zooms in on Jesus at the beginning and zooms out on his dead body in the end. But The resurrection scene, with Jesus’ sideways exit, appears as something entirely new.

And that should remind of the true meaning of a Dues Ex Machina. It refers to the convention in ancient Greek tragedy to hoist gods onto the stage to solve these unsolvable problems. And in that sense the Resurrection is precisely that. It’s a Deus Ex Machina in the true sense of the term, it is humanly speaking utterly unexpected. To the Mayans, the arrival of the Spanish as strange as aliens landing on the earth. Or as Gibson appears to allude, the second coming of Christ.

For Gibson, Revelation doesn’t just happen once but again and again.

The one who compassionately suffered with the victim has now become their oppressor’s judge.

Hi, this is Matt. I want to do something different today. I usually make videos analyzing the symbolic meaning in films, but today I wanted to talk about how I know and how you can know a film’s symbolic meaning?

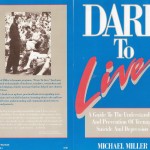

If you read the comments on this channel, you will see that I regularly get accused of imposing my beliefs on these movies that I am finding in them something that isn’t really there. Of course, my believing that Andy represents Jesus, Chigurh symbolizes death, the groundhog symbolizes Phil, Max’s Muzzle signifies a beak, and Wilson represents Chuck’s old self but does not make it so. So how I do know that this is more than likely what the filmmakers had in mind? The answer begins with language.

We as humans by nature makers and interpreters of symbols. We listen because we understand. We speak because we expect to be understood, and that’s not all that different from what screenwriters and directors do. They use and invest images with symbolic meaning because they expect us to understand them, and they can do this because it’s something that we do every day.

The words we used are symbols. Take the word “hand” for instance, it’s not the thing itself, but a spoken or written representation of something else. Our cultural context has invest the sound and our combination of letters with meaning, and because words are symbols, not the thing itself, they can and often have a variety of meanings. A list which can grow as words pick up new associations in new context. This is how for instance giving someone a hand came to refer as not to the literal act of cutting out that body part, but instead to help or applause. The specific context was the implicit key by which the hearer understood the speaker’s intent, and from a single usage, the meaning spread to the cultural list of meanings. It’s only in context that we actually know a word’s meaning. A word outside our context means nothing to us, and without some additional context, we simply assume our cultures most common use. Determining if another meaning is intended as a matter of accounting for all the contextual evidence, the more coherence we find increases our confidence that we have indeed understood as speaker’s intent.

In film, images work the same way. An image is simply the thing itself unless context suggests some other sense. Screenwriters and directors invest images with symbolic meaning in a same way we do words by connecting them to other things – a spoken metaphor, a comparison may be between two things becomes a possible meaning when the physical image is shown later on in the film, but metaphors can also be done visually, the effect of cutting between two images places an additional or equal sign between them. Similarities and or contrasts not necessarily shown next to each other can produce the same effect.

But screenwriters and directors also pick images for their pre-loaded cultural associations. Other movies, television shows, historical events, books, philosophical ideas as well as universal experiences already inform us of an image’s possible meanings.

We don’t have to ask a filmmaker what they thought to know what they were thinking; the film tells us in the same way a sentence tells us the thoughts of a speaker. Just as a safecracker listens and considers the sound of a lock testing out hypothesis by trial and error, so we too come to understand a filmmaker’s intent by linking up meaning in film. Since we intuitively understand how symbolism in language works, symbolism is working its magic on each of us.