My sister has a hidden door in her room. On the surface it appears ordinary but the unusual detail and you’ll want to look for a way inside. In Hollywood’s recent adaptation of Sherlock Holmes, Holmes is tipped off to the presence of such a door by an unusual draft.

I love the mystery secret doors contain. Perhaps that’s why I enjoy the Gospel of John so much. The Gospel of John in a similar manner contains hidden doors.

Cracks in the Surface of John

In John, characters regularly fail to perceive the true significance of a word or an event the first time around. At least eighteen times, Jesus’ use of an ambiguous or metaphorical word causes his dialogue partner to stumble over His meaning. This in turn leads Jesus or the narrator to clarify what has been said.

Take Jesus statement concerning the destruction of the temple in John chapter 2 for example. When the Jews ask Jesus for a sign to prove his authority, Jesus calls them to destroy this temple and he will raise it up in three days. The immediate context leads the Jews to associate “temple” with the temple in which the events occur. The narrator, however, interjects, informing the reader that he was referring to his body.

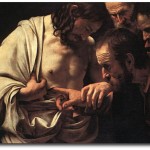

A similar misunderstanding and correction occurs in Jesus call for Nicodimus to be “born again.” Nicodimus scoffs at the apparent obsertaity of a man returning to his mother’s womb. Jesus, however, restates his meaning, “unless one is born of water and the Spirit,” he cannot enter the Kingdom of God.

Or finally look to the example found in Jesus conversation with the Woman by the Well. Jesus offers the woman “living water” and she wonders how he will retrieve water from the depths of the well.

The cumulative effect of these misunderstandings teaches the reader how to read the gospel. As Randy Culpepper states,

Readers are therefore oriented to the level on which the gospel’s language is to be understood and warned that failure to understand identifies them with the characterization of the Jews and the others who cannot interpret the gospel’s language correctly.

The author does not spell out for the reader every time these misunderstandings occur. Often he leaves it to the perceptive reader to fill in the gaps.

The contrast between surface and significance can be found in the Synoptic’s portrait but its fundamental to John. Matthew, Mark and Luke each record that during Jesus’ ministry He engaged in a number of symbolic sayings, a method of teaching they call parables. They understood the parables not just as something which revealed the truth but something which also concealed it. According to the gospels when the disciples questioned Jesus about them he said,

To you has been given the mystery of the kingdom of God, but those who are outside get everything in parables, so that ‘while seeing, they may see and not perceive, and while hearing, they may hear and not understand, otherwise they might return and be forgiven.

Here Jesus quotes from Isaiah, a passage that for Paul and others explained why the Jews failed to recognize Him. For the synoptic authors the parables existed to judge the people. For those who desired to know an interpretation was supplied but for those who refused to follow the meaning of Jesus’ teaching remained allusive.

While John has no parables to speak of he does not abandon the polar notions of revelation and concealment. John also appeals to this passage from Isaiah. At the end of chapter twelve, the conclusion of what C.H. Dodd and others have called the book of Signs, John summarizes the Jews response to Jesus.

But though he had performed so many signs before them, yet they were not believing in Him. This was to fulfill the word of Isaiah…”He has blinded their eyes and He hardened their heart, so that they would not see with their eyes and perceive with their heart, and be converted and I heal them.

Here it’s not simply Jesus’ words which offer an evaluative challenge but Christ’s actions. The shift in terminology from the Synoptics bears this out. Though the Synoptics consistently refer to the acts which Jesus performed as miracles, John labels them signs. Unlike miracles (dynameis), a sign points to something else.

This is the way John understands them. For instance in John the feeding of the five thousand becomes a vehicle for Christ declaring himself the bread of life and His declaration to be the light of the world precedes him opening the eyes of a man born blind. The failure of the Jews was not simply a misreading of the scriptures it was a misreading of Christ’s deeds.

For John, concealment and revelation even extends beyond Jesus’ teaching and actions. It is born in the fundamental separation of God and man and the Father’s self disclosure in Christ.

At its core the fourth gospel depicts a universe divided; the world “above” separated from the world “below,” the tangible separated from the imperceptible. For instance in John 3:12, Christ distinguishes between “earthly things” and “heavenly things” and in 8:23 He differentiate Himself from His opponents, stating, “You are from below (ka,tw), I am from above (a;nw) you are of this world, I am not of this world.”

For John the separation of the higher and lower world is a central problem confronting humanity. This higher world represents an intangible reality which man cannot see. The prologue asserts “No one has seen God at any time” (1:18). Yet John goes on to claim that Jesus’ physical presence “explained” or “made known” the invisible God (1:14, 18). For John, Jesus is the incarnation of the Logos, a bridge between the known and the unknown. To see him is to see the Father (14:) but once again the Jews lacking in spiritual insight saw only a man (10:.