I’ll never forget sweet Grandma Lydia’s awkward pause as she read 1 Samuel 20:30 from the Living Bible.

“Saul boiled with rage. “You son of a b…

You could see that she didn’t know what to do. She stood there in front of our Sunday School class, a blush spreading across her cheeks.

“Come on,” I said with a smile. “If it’s in the Bible its OK to say.”

She never read it. God bless her!

I like to open discussions of translation with this particular rendering of scripture. It’s ear-opening to say the least.

It certainly amused me, finding as I did in my daily devotions at the age of 17. I approached my youth pastor the next Sunday, handed him my bible and said, “God gave me 1 Samuel 20:30 as a word for you” :0.

Don’t worry. He eventually forgave me.

Such an out-of-place word causes us to wonder about the differences between Bible versions. What makes a good translation? Is there one better than the other?

What do you want most in a translation? Every time I ask my students this question it comes down to these two issues:

Accuracy: we want a translation that is faithful to the original language.

Clarity: we want a translation that is easy to read and understand.

The problem for translators, however, is that these two desires are not easy to meet with equity. Accuracy and clarity are like two sides of a scale, focus too much on one and the other side gets out of balance.

Words in one language, for instance, don’t have the same range of meaning that they do in another. In John 3:3 for instance, Jesus tells Nicodimus, “no one can see the Kingdom of God unless they are born anothen.” The word anothen means a “second time” but it also means “from above.” No English word possesses this range of meaning. Any single word used in translation will at least partially obscure its meaning.

Likewise, the ordering of words in translation can upset the balance of accuracy and clarity. We say, “This is my friend.” We don’t say, “Friend my this is.” But in Hebrew and Greek the later construction is quite natural and reveals a great deal about the the meaning of the sentence. We know that stressing different words changes the implication of a sentence.

- This is my friend. Neutral

- This is my friend. As opposed to someone else’s friend.

- This is my friend. As opposed to my enemy or something else.

The free ordering of words in Hebrew and Greek reveal the stress on any given word. It tells us what ideas are more important and what ideas are less. Reordering the words so they make sense in English without losing meaning can be difficult.

Finding the right balance between accuracy and clarity is the reason we find so many versions today. To this end, Bible translations break down into three groups, each representing a particular method.

Word-For-Word translations (a.k.a formal equivalence): The translator tries to find the nearest equivalent words and to place them in as close a corresponding order to the original text as possible. The NASB, ESV, KJV and NKJV follow this translation method.

Thought-For-Thought translations (a.k.a. dynamic equivalence): The translator attempts to grasp the meaning of the sentence or phrase and to translate that meaning in whatever words or phrases that are deemed most useful. The NIV, TNIV, NET and the NLT follow this more modern method.

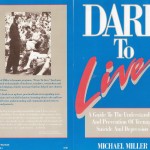

Transliterations: These “translators” follow a Thought-For-Thought method but begin with a Word-For-Word translation instead of the Greek text. They are twice removed from the original language. Like a copy of a copy they are interpretations on top of translations. The Message and the Living Bible are the more popular representations of this group.

A Word-For-Word translation of 1 Samuel 20:30 reads,

Then Saul’s anger burned against Jonathan and he said to him, ‘You son of a perverse rebellious woman!’ (NASB)

Though it may not be a Word-For-Word rendering, I think the Living Bible rendering captures Saul’s thought quite nicely.

What do you think?

Pingback: Why You Shouldn’t Read the King James Version | Logos Made Flesh

Pingback: The New Voice Bible | Logos Made Flesh